- Home

- Maggie Alderson

The Scent of You Page 5

The Scent of You Read online

Page 5

That thought prompted me to ask how often they wear scent, and most of them said only for special occasions – that old chestnut.

‘What are you saving it for?’ I asked cheekily, and luckily they got the joke. So that’s a reminder to us all: don’t save your favourite perfumes for ‘best’; wear them whenever you feel like it.

So the smells I associate with the Elders are freshly cut garden flower arrangements – roses, lilac and endless sweet peas and the fougère hints of random greenery lavishly added to the vases, in the Constance Spry style.

Also, modest shop-bought flowers, particularly daffodils, tulips and freesias, which are such an economical way to brighten a room for that thrifty generation.

My scents for the elders are:

Lavender by Yardley

Blue Grass by Elizabeth Arden

Rose in Wonderland by Atkinsons

Femme by Rochas

Ostara by Penhaligon’s

Tweed by Lenthéric (A mention of this elicited a big response at the event; it seemed all the women had worn it at some time and had happy associations with it. I do wish they would re-release it in the original tweed fabric-effect box.)

The men in this age group are the last of the true British gentlemen, so especially for them:

Old Spice

St Johns Bay Rum by St Johns Fragrance Company

Royal Mayfair by Creed

COMMENTS

LuxuryGal: This is so great! I’m going to do an event like this at my mom’s retirement home. She’s worn Youth Dew since the 1950s too! I keep buying her new perfumes, but she’ll only wear that one. I wear a different one every day, just like you.

FragrantCloud: Perhaps I’ll get to come to LA sometime and I can do it for you! Polly x

TheSpritzer: I’d love to hear more about Mr Mitsouko. Imagine if he still had a bottle of his mother’s original brew . . . It’s changed so much since then with all the restrictions on perfume ingredients. I would love to have smelled it in the 1930s as he did.

FragrantCloud: I know! I thought the same thing . . .

LeichhardtLori: Give Daphne our love! What did she wear for this event?

FragrantCloud: Hi Lolster! I will. Fracas . . . She did my hair and make-up. You would have cracked up. I looked like Lady Penelope, but better than I normally look LOL. Skype soon? xxxxx

EastLondonNostrils: Love the picture of your mum’s perfumes. Please will you do an event in London with her?

FragrantCloud: She’d love that!

Tuesday, 5 January

Polly was passing her time waiting for Clemmie at the lunch venue her daughter had chosen, a concrete-walled space right on Shoreditch High Street, memorising the ridiculous items on the menu. The combinations on offer were almost as bonkers as the clean-eating brunch, but at least Clemmie’s vegetarian diet was inspired by wanting to cut back on CO2 emissions, rather than calories.

Leaning down to give Digger a pat, she reminded herself not to let it slip that she’d driven there. Clemmie would not approve, but Polly still wasn’t used to taking public transport with the dog. Another major inconvenience of having to look after him. She was terrified he was going to jump down the gap between the Tube train and the platform, or let off on a bus with one of his signature fragrances.

And it was handy this restaurant actually allowed dogs in – she’d rung ahead to check, because it was amazing how many places didn’t and she couldn’t leave him at home. David used to take Digger to work with him every day and the poor hound wasn’t used to spending much time alone. The one time Polly had tried leaving him there since David had gone away, she’d come back to a furious neighbour, complaining Digger had howled all day.

She was glad he was behaving now, lying under the table, his head resting on one of her feet. At least that felt nice and cosy on a freezing January day. She’d just reached down to scratch his neck when she saw Clemmie walk through the restaurant door in a fluster of coat, scarve, gloves and bobble hat, her cheeks bright pink.

‘Sorry I’m late, Mummy, the train was crap,’ she said, rushing over to the table and giving Polly a hug and a warm kiss, before she started the long process of taking off her layers.

‘I take it the Siberian winds are blowing into Cambridge, then,’ said Polly, remembering the uniquely bitter winter air in her childhood town.

‘Straight from Omsk without stopping,’ said Clemmie, squeezing into what was left of her seat after she’d draped it with clothing. ‘I’m going to knit myself a full-face balaclava. Cycling to lectures from the flat is a major endurance event with that wind blowing in your face. It’s enough to make me want to get a car. Nearly.’

Polly smiled at her. Definitely keep quiet about driving there.

‘What’s the vegan spesh today?’ asked Clemmie. ‘Have you looked?’

‘A braised aubergine and quinoa tacu-tacu pancake, with an avocado and amaranth superfood stack,’ said Polly.

‘Mmmm,’ said Clemmie, ‘that sounds great.’

‘What is tacu tacu?’ asked Polly, thinking it would be easier to order the same thing than have a long discussion about methane gases and deforestation.

‘It’s this yummy Peruvian thing, where they mix up leftover rice and beans and fry it into a sort of patty,’ said Clemmie.

‘Peruvian bubble and squeak, then?’ said Polly, and Clemmie had the good nature to laugh.

‘When do lectures start again?’ asked Polly, immediately hoping it didn’t come over too obviously as a suggestion that Clemmie come and spend some time at home before the term officially began. Which was exactly what it was.

Two nights over Christmas, with everyone trying to pretend it wasn’t extremely bizarre that David wasn’t there, hadn’t been nearly enough Clemmie time for Polly. Especially as she’d brought her boyfriend Bruno with her. Not that Polly had a problem with Bruno, he seemed a very nice young man – and as Lucas had said, teasing his big sister about her hunky new chap, ‘What was it about the rich Italian Cambridge rowing Blue which attracted you to Bruno?’

It was just that particular year, after Daphne had gone home, Polly couldn’t help wanting to spend some time just with her children. Coming so soon after David’s surprising departure, Christmas had felt like a time for hunkering down together, rather than welcoming people in. She still had all David’s presents, which had been wrapped up, ready, before he went. She’d stuffed them in a cupboard on Christmas morning, suddenly realising how weird it would have been to have them still sitting under the tree when all the other packages had been opened.

‘Oh, there’s no official classes for another couple of weeks,’ said Clemmie, ‘but we go straight into some really heavy tests, so I’ve got to study like crazy. It’s hard work, this doctor-becoming business.’

‘But it will be so worth it in the end,’ said Polly, pride in her clever daughter’s academic commitment going some way towards soothing her disappointment. Clemmie had decided she was going to be a doctor even before she became a vegetarian, at the age of twelve, and once she made her mind up about something there were no halts and no reversals. She was like her father in that way.

Lucas’s university choice of music production had been a lot more vague – he played bass guitar and had thought the course sounded ‘quite cool’ – but he’d make his own way, even if it was the long way round: a bit like her becoming a yoga teacher and now a perfume blogger.

She and Clemmie placed their orders – two vegan specials and two tap waters, not exactly living it large – and Polly asked the usual interested-parent questions about Bruno and other friends of Clemmie’s, until she hardly knew what was coming out of her mouth for the clamour in her head of wanting to talk to Clemmie about David.

She was finding it hard to eat, her mouth dry with anxiety from trying to stop herself mentioning him.

It wasn’t that she felt she had to stick to his ridiculous request for her not to talk to the kids about him – she didn’t think she owed him that courtesy

in the circs – but for fear of upsetting Clemmie. What would it be like for Clemmie to know her father actively wanted no contact with any of them for six months?

Eventually Polly found that the cutlery had dropped from her hands and she was close to tears.

‘I’ve got to talk to you about your dad,’ she said. ‘I managed to hold it together over Christmas for everyone’s sake, but I can’t keep it up any more. I’m going mad. I’ve been married to him for over twenty years and I don’t know where he is, let alone why he’s left . . .’

Clemmie’s face immediately looked stricken. She leaned across the table and took her mother’s hand, then lifted up her napkin and wiped away the tear that had rolled down Polly’s cheek.

‘Oh, Mum,’ said Clemmie, ‘I thought you were being strong, and I didn’t want to bring it up because I felt I had to take the lead from you. I’m not surprised you’re confused, it’s so unfair on you.’

Polly wondered how much Clemmie knew. Was she aware that David wanted no contact with any of them? He had been so dramatic about the dire consequences of discussing the situation with anyone – but how could that apply to their own children?

‘I don’t even know what he’s told you,’ Polly said. ‘He asked me not to discuss it with you and Lucas, which is why I spent Christmas with an invisible gag on, but are we really supposed to stop talking to each other for his convenience? It’s simply not fair.’

Clemmie looked thoughtful for a moment before she answered.

‘Nothing about this is fair,’ said Clemmie. ‘It’s terrible for you – and for me and Lucas. The only thing we can hang on to is that he must have been really desperate to do this to us.’

‘Desperate about what? And how could he not trust us?’ asked Polly, brushing away another tear and trying to pull herself together. ‘Whatever it is, anything would be better than this. It’s the not knowing that I can’t bear.’

Clemmie had tears in her eyes now.

‘I just don’t know, Mummy,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘I don’t know what to say and I don’t know what to think. How’s Lucas coping with it?’

‘Badly,’ said Polly. ‘You know what he’s like. He keeps it all bottled up and then it comes bubbling out and he has a freak-out. I thought it was amusing when he got roaring drunk on New Year’s Eve and came rolling home the next day, but now he seems to be doing that every night, which isn’t funny at all. It really hasn’t been a great end to his first term at uni. Did David even think about that? Apparently not. Lucas is only nineteen and he’s young for his age. You’ve always been so mature, Clemmie. It’s like you got all the common sense and your brother got none. So I’m worried about him, on top of everything else.’

‘I’ll ring him,’ said Clemmie.

There was something about the way she said it that suddenly irritated Polly. Like that would sort it out. One phone call from Big Sister. What Clemmie actually needed to do was to come home with Polly and sit down with her and Lucas to talk about this. Make a plan. It wasn’t a quick-fix-phone-call kind of situation. And the way her daughter was staring down at her food, stirring it around with her fork, rather than looking Polly in the eye made her suddenly suspicious.

‘Do you know where your father is, Clemmie?’ she said firmly.

Clemmie immediately screwed up her eyes, then nodded, very quickly.

‘Where?’ asked Polly, trying not to let her raging anger with David come into her voice and unfairly hurt her daughter.

‘He’s in London,’ said Clemmie, very quietly, looking down at her hands and then up again, sighing deeply.

‘London?’ said Polly slowly. ‘Has he been here all the time?’ ‘No,’ said Clemmie. ‘He’s been in Turkey.’

‘Turkey?’ said Polly. ‘I thought he was supposed to be in Nepal.’

‘He told me it was Turkey,’ said Clemmie. ‘Anyway, he came back to London on New Year’s Eve.’

When I was all alone, looking up at the moon, wishing I was in his arms, thought Polly.

‘Well, where’s he staying in London? Why hasn’t he come home?’ she pressed.

‘I don’t know about any of that, I just know he’s here and he’s going away again tomorrow, he just had to come back quickly for some reason, to get some stuff he needs . . .’

‘Some stuff?’ said Polly. ‘From the house?’

Clemmie nodded, looking quite sick.

‘Well, when’s he going to come round?’ asked Polly. ‘I’ll make a cake.’

Clemmie looked even more uneasy and Polly felt slightly ashamed for being sarcastic to her daughter, but she didn’t feel quite in charge of herself.

Clemmie swallowed before answering.

‘He’s there now,’ she said.

Polly just looked at her daughter for a moment as her stomach seemed to drop away.

‘Are you serious?’ she said quietly.

Clemmie nodded again, a tear now running down her cheek.

‘Is this a set-up?’ asked Polly.

‘Not exactly,’ said Clemmie, looking wretched.

‘But he asked you if you knew when I might be out of the house?’

Clemmie nodded silently again.

The nodding was really beginning to irritate Polly, which she knew was irrational and a distraction from the real issue. She sat in silence, finding it very hard to take it all in and not really wanting to; it was so very hurtful.

‘So David is making you collude with him to avoid me?’ she said eventually.

‘Oh, Mum, don’t take it like that,’ said Clemmie.

‘What other way is there to take it?’ said Polly. ‘Does Lucas know he’s there? Are they there together, right now, having some quality father-and-son time?’

‘No,’ said Clemmie, looking even more ashamed. ‘I knew Lucas was going to be out today too.’

Polly felt a flash of rage go through her. It was a bit like an electric shock and made her feel almost afraid of what she might say, in public, to her daughter.

She fished hastily in her bag, pulled two twenty-pound notes out of her wallet, threw them on the table and stood up.

‘As, unlike me, it seems you are allowed to talk to him, will you please give your father a message, Clemmie?’ she said, trying to keep her voice low and level. ‘Will you tell him he’s a total arsehole? And while you’re doing it, have a think yourself about which parent you might like to be loyal to. The one who’s been abandoned with no explanation, or the one who’s just fucked off to do his own thing for no good reason? And you might like to give your brother a moment’s thought too. He’s a lot more sensitive than you are.’

She picked up her coat and bag, and had just started heading towards the door when she remembered Digger. She turned back to see he’d stood up and was looking at her expectantly.

She bent down and picked up the end of his lead and handed it to Clemmie.

‘And you can give him his dog to look after too. Goodbye.’

‘Mum, wait!’ cried Clemmie and Polly heard her chair crash to the floor as she stood up, weighed down as it was by all her coats and scarves.

Polly kept walking as fast as she could without actually breaking into a trot. To her great relief, just as she got to the restaurant door, a bus pulled up at the stop right outside.

She jumped on it without looking at the number. She could go back for the car later.

She heard Clemmie call out to her again as the bus doors closed, but she didn’t look round. Then she heard a yap and her head turned despite itself. Clemmie was looking distraught, chasing Digger, who was running after the bus.

She felt a pang of guilt for putting her daughter in that situation – and another for Digger – then dismissed them both. She was sure the dog had enough sense of self-preservation not to run into the traffic, and as for Clemmie, what she’d done was just plain wrong.

She’d colluded with her father to help him avoid seeing Polly, and Polly just couldn’t let that go. Of course, she would over time. She wasn’t

going to lose her daughter as well as her husband – and she did understand how torn Clemmie must be between her parents in this bizarre situation. But Clemmie was an adult now; she had to get used to being treated like one.

Polly’s phone rang. She knew it was her daughter without even looking. She dropped the call and sent her a text.

Not now, Clemmie. I’ll call you later when I’m ready to talk about this. You must understand how much this has hurt me on top of everything else. Mum

No kisses. It was harsh, but this was an exceptional situation. Exceptionally hurtful.

As the bus turned into Commercial Street, Polly gazed unseeingly out of the window, until her attention was grabbed by a man walking by with an adorable little girl of about four holding his hand and skipping by his side. She looked as though she was singing.

The poignancy of the moment was like a fist to Polly’s gut, a sharp reminder that Clemmie had grown up with a strong case of my-heart-belongs-to-Daddy – which Polly really couldn’t blame her for, because she’d been exactly the same herself.

Daphne had been so self-obsessed and preoccupied with her career that Polly’s steady, thoughtful father had been a much safer haven during her own childhood. And unlike many academics, who shut themselves away to work, he hadn’t minded being interrupted.

In fact, Polly had very fond memories of sitting on his knee while he typed, or being given what felt like the very important job of collecting particular books from the sofa, floor, windowsill or wherever they were perched, and opening them for him at the marked pages.

He’d put her name in the acknowledgments in several of his books – ‘A special thank you to Polly, my delightful personal elf’ was one she particularly remembered – and now those dusty volumes were probably her most treasured possessions.

But while Polly understood Clemmie’s special relationship with her dad – and also had to acknowledge that she harboured a special kind of tenderness for Lucas, not more love than she had for Clemmie, just differently flavoured – she still felt this was a terrible betrayal.

The Scent of You

The Scent of You Evangeline Wish Keeper's Helper

Evangeline Wish Keeper's Helper How to Break Your Own Heart

How to Break Your Own Heart The GoMo

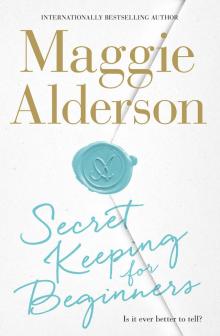

The GoMo Secret Keeping for Beginners

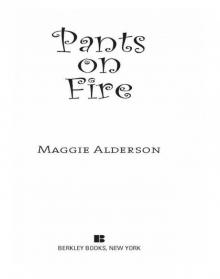

Secret Keeping for Beginners Pants on Fire

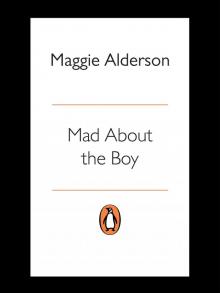

Pants on Fire Mad About the Boy

Mad About the Boy Handbags and Gladrags

Handbags and Gladrags Cents and Sensibility

Cents and Sensibility