- Home

- Maggie Alderson

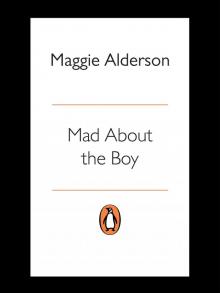

Mad About the Boy Page 3

Mad About the Boy Read online

Page 3

It could be described as ‘absolute waterfront’ – a local expression I found hilarious – but it actually bordered only about six feet of water, so the house was like a pile of narrow boxes, stacked up, with a series of staggered balconies looking over the expensive liquid view.

The views were magnificent – Sydney Harbour still knocked me out – but the house was horrid to be in. Surrounded way too closely by other piles of concrete boxes, it seemed to be permanently in the shade and smelled strongly of mildew, and you were constantly going up and down dark stairs, between the floors. Worst of all, as far as I was concerned, the whole thing seemed to be marble. There were marble floors, marble walls, marble tables and marble ashtrays. It was like being in a funeral monuments showroom, and a plethora of faded and dusty silk flower arrangements added to the effect.

There wasn’t much furniture to speak of, just a couple of very large, very ugly sofas down either side of the main drawing room, with a marble coffee table plonked in the middle, covered in remote controls. In the dining room there was a lit-up bar and a monstrous smoked-glass and brass dining table.

‘David says he doesn’t know why he bought a glass table,’ said Nikki, flashing her devastating smile. ‘He can’t grope anyone under it without me seeing.’

I smiled weakly.

There weren’t any paintings, any real flowers, or any books, in the whole place – just a few framed posters, including the famous knicker-less tennis babe in David’s den. Nikki proudly demonstrated how a marble panel in the same room slid back, at the push of a button, to reveal his collection of videos, which included Teenage Sluts 5 and Asian Teens 3, among much more porno, as well as the more usual Lethal Weapon and Pretty Woman, although when I looked again I realized it was actually Titty Woman.

To make the most of such delightful videos, they had the largest televisions I’d ever seen – and one in just about every room.

Their bedroom was enormous, with a huge bed and, all too predictably, mirrors on the ceiling. There was also a video camera, set up on a tripod, pointing at the bed and linked to the TV. I didn’t know where to look, but Nikki clearly didn’t give a damn.

Leading off it there was an en suite bathroom the size of our drawing room, with his and hers basins, showers and even loos. The towels had ‘His’ and ‘Mine’ embroidered on them, I noticed. The curtains in every room were those horrid vertical blinds, opening and closing electronically. They looked dirty.

Nowhere was there any sign of children, which I found almost sinister. I did my best to keep Tom’s toys under control in our place, but his drawings were all over the kitchen, his clay models proudly displayed on the mantelpiece and there were always a few plastic dinosaurs underfoot and Lego works in progress lying around. I liked his child energy in the place. Nikki clearly did not feel the same.

At the end of the tour of this soulless house, I was truly speechless, which Nikki took as a great compliment.

‘It is a pretty amazing property, I know,’ she said smugly, serving me Diet Coke in an elaborate cut-glass goblet on one of the many cold dark balconies. ‘But I’d like it to have more of that classy English feeling your house has, Antonia. What do you suggest?’

Demolition was the first word that came into my head, but I managed to stop it coming out of my mouth.

‘I’d have to give it some thought, Nikki,’ I said, playing for time. ‘It’s not the kind of, er, property I’m used to working with. I’ve always decorated old houses before and old furniture sort of goes in them.’

She gave me one of her assessing looks.

‘Second-hand furniture?’ she said quickly.

‘Well, I suppose it is …’

‘I wouldn’t want second-hand furniture in my house. Someone else’s dirty old cast-offs,’ she was pulling a ‘yuk’ face. ‘This is all new furniture,’ she said proudly.

‘I’m sure it is,’ I said. ‘But if you want the look I have in my house, Nikki, it will have to be old furniture. My French armoire is probably 150 years old, maybe more. I wasn’t the first person to own it.’

She took it all in.

‘Hmmm,’ she said. ‘I’d never thought of that. I’ve just never fancied second-hand stuff. I’ll have to think about it. Can’t you get new stuff and make it look old? Bang it with a hammer?’

‘Yes, you can do that. People do, but it’s not what I do. It doesn’t have integrity for me. What I like about the old furniture I buy is that it has character and a history – a patina which makes it unique. If you go and buy something new, it’s exactly the same as all the other ones.’

She frowned at me.

‘But at least you know what you’re getting,’ she said.

‘It’s not knowing what I’m going to get that keeps me interested,’ I replied.

‘So where do you get all that old stuff, anyway?’ she said, pouring more Diet Coke. ‘Does it all come from France?’

I was not about to reveal my sources to her.

‘From France and various other places, here and there,’ I said. ‘You just sort of come across it.’

She looked deeply unimpressed.

‘Well, I like them chairs of yours, anyway. I want some of them. I think they’d look good in there. Can you get me some?’

She was beginning to piss me off.

‘No, I can’t,’ I said, firmly. ‘I got them out of a filthy old barn in southern Ireland. They were covered in chicken shit. I restored them and painted them myself, as I told you. I could try to find you something similar. But not with that smoked-glass table. Or your china. Or your cutlery.’

She looked furious.

‘What’s wrong with my cutlery? That cutlery cost a lot of money. It’s a hundred per cent real brass.’

‘I’m sure it cost a lot of money,’ I said. ‘But it wouldn’t go with Gustavian chairs and the combination would not enhance my credibility as a decorator in Sydney.’

We glared at each other like two cats having a stand-off. Once again she narrowed her emerald green eyes. They were such a give-away, you could practically see her calculating behind them. I thought if I could just focus on it, I’d see a little Reuter screen in there, blinking as she worked out the pros and cons of various actions and their effects on her stock price.

She clearly decided keeping it nice was the best option at this stage and veered off on a new tack, probing me about Hugo and his family. I just went along with it, making the answers as gnomic as I could, until eventually I had the excuse of collecting Tom from school as a pretext to leave.

The next morning she rang and asked if I would get her some of ‘them chairs’ if she ‘let me’ redecorate her entire dining room. Having established I could remove, or at least paint over, the marble and replace the table, the china and the cutlery, I agreed. I had to start somewhere in Sydney.

Big mistake.

3

Once I got stuck into redecorating Nikki’s dining room, I began to have a really good time. I’d forgotten how much I enjoyed the chase of finding the right pieces for a space, and the challenge of her ghastly house actually turned out to make it more fun. I also had a tax deductible excuse to drive around Sydney and environs, checking out possible sources – and acquiring stock for my shop, which I was planning to open in a few weeks.

The only problem was that Nikki was always trying to come with me. I’d take her my work-in-progress scrapbooks of swatches and Polaroids of possible items, as I had done with all my clients at home, but she was always telling me how much more ‘efficient’ it would be, if she just came along with me on my buying trips.

In the end I had to stop answering my mobile, to shake her off. Hugo had to text me when he wanted to get hold of me. Luckily she didn’t seem to have the hang of that yet.

But still I couldn’t escape her. One morning I went out to Wally’s Where House, a seriously grungy used-furniture depot on Sydney’s southern outskirts, where I wanted to have another look at some chairs I thought might work for Nikki’s

dining room, with some major overhauling. I was sitting in the car park, waiting for it to open – dealers always get there before places open – when there was a tap on my car window. It was Nikki.

‘What a coincidence,’ she was saying. ‘I’d heard about this place and I thought I’d pop down here and take a look and here you are …’

I just looked back at her in amazement. Considering her attitude to old furniture, I found it very unlikely that a trip to this junk heap would be her idea of a fun day out. Even I – who would happily dodge pigeon droppings from above and rats underfoot, to get into a promising-looking old shed – sometimes found myself repelled by some of the old sofas and mattresses I encountered down there.

I got out of the car and looked her over. She was wearing an immaculately pressed white linen shirt, tied at the waist, and matching pants. No one who had heard of Wally’s – and there was a small group of in-the-know regulars – would ever have gone there dressed in white.

Most of the time, I’m pretty wimpy about standing up to people, but every now and again a flinty little core in me comes out. It came out then.

I looked Nikki straight in her contact lenses.

‘Did you follow me here?’ I asked her.

She looked back at me, doing one of her instant stock analyses.

‘Yes,’ she said.

I shook my head.

‘You’re quite a piece of work, Nikki,’ I told her.

She took it as a compliment and beamed her famous smile at me.

‘I know,’ she said, happily. ‘I always get what I want.’

‘Well, as you’re here, I suppose I’ll have to let you come round with me,’ I said. ‘But I don’t mind telling you, you have broken a fundamental rule of trust between decorator and client.’

She gave me another shot of the smile. Like everyone else she worked it on, I just sighed indulgently and let her have her own way.

Of course, I was thrilled to see the grin wiped off her face when she saw what the furniture warehouse was like inside. If you don’t have the inborn ability to see beyond the desperate shabbiness and the general smell of failure, death and decay, to the potential of a filthy old object, those second-hand barns are like graveyards of broken lives. But to me they were Aladdin’s caves, full of promise just waiting to be unleashed – and prices just waiting to be multiplied by a hundred.

And I should say here, I had no qualms about putting outrageous mark-ups on the things I found in those junk dens. I was the one with the eye for it and the stomach for the hunt and, on the whole, my clients were just happy to have a lovely old chair, or kitchen table, without having to do anything for it apart from sign the cheque.

To my great satisfaction, Nikki was totally bewildered by it all. I don’t know what she had expected, but this definitely wasn’t it.

‘Surely you’re not going to buy anything for my house in here?’ she asked, picking her way between the towering piles, horrified.

‘Oh no,’ I said, fingers crossed in my pockets. ‘But I might buy stock for my shop.’ She turned and looked at me quickly.

‘Are you definitely opening a shop then?’

I nodded. ‘Yeah. I’ve taken a space in the south end of Moncur Street, you know, the bit that goes towards Centennial Park?’

‘Isn’t it a bit dead down there? Couldn’t you get something on Queen Street? It would be much better for your market,’ said Nikki, with a savvy that surprised me.

‘I looked at a great place on Queen Street,’ I told her. ‘But I couldn’t afford it. So I’ll just have to hope that word of mouth will bring customers in – like all the people who come for dinner at your place and ask who did the amazing make-over on the dining room.’

I tried flashing my own version of her smile. She looked pleased at the thought of the attention the dining room would bring her and shifty at the same time.

‘Is that all it takes to make a shop successful?’ she asked.

I laughed.

‘I wish. I’ll also have to work on getting some press coverage in the good interiors mags and, most importantly, I need to sell things that people want to buy. Like this.’

I held up a filthy little yellow jug, which had some nasty-looking old forks in it. She looked at it, scowling with disgust, clearly mystified why I thought anyone would want such a horrible object. I shrugged. I wasn’t going to tell her about the five or six other assorted yellow vases and jugs I had already collected from various motley sources, that would make a wonderful group on a table, sitting on the old linen tablecloth, hand-embroidered with primroses, that I had found the day before in a charity shop in Bondi Junction.

I chucked the forks into a nearby bucket and looked at the bottom of the jug. It was marked $1, but by the time I’d washed it and styled it, I reckoned I’d be able to sell it for $60. Bingo. I made a note to that effect – buy price, sell price – in my trusty exercise book, which Nikki immediately tried to see.

‘Nosy!’ I told her, snatching the book away, and we carried on around the barn, with me fearlessly diving into sinister cardboard boxes and looking under vile old beds, while Nikki tried not to touch anything. I was gratified to notice that she had about a yard of filthy old cobwebs hanging off her perfect white linen arse as we left.

After that, Nikki stopped asking to come on my buying trips, but she was still very inquisitive about every step of the transformation of her appalling dining room into a rather opulent salon, in a sort of faux St Petersburg style.

It worked in the space, because I had deliberately made it like a camp 1960s filmset version of Russe luxe. ‘Chic ironique’ Hugo called it, when he came over for a look, which seemed to delight Nikki, although I can’t imagine she really knew what it meant. Either way, the room was cute, quirky, warm and very nice to sit in. And she got her grey chairs.

They were the ones from Wally’s, which amused me intensely, but she would never have recognized them after I’d had them stripped in an acid bath and changed the front legs. Then I had painted them my signature grey and upholstered them with a grey and white satin-stripe silk. They were gorgeous. Cost me $10 each from Wally’s and $90 each, fully finished. They cost her $3,000 for ten. That’s showbiz.

On the day I came to put the final finishing touches to the room – she was having a ‘launch party’ for it that evening and it meant a lot to both of us that it was perfect – she showed me that the paint on one of the chair legs had been badly chipped. She said the man who’d come to hang the chandelier (I got it from a sale of the fittings from a communist-era Polish cruise ship – it was fabulous) had done it.

I touched it up quickly from the end of a tin of paint I had in the car. Then, while I was rushing to lay the table and arrange the flowers ready for the photographer from Belle magazine, who was coming to shoot the room just before the party, Nikki persuaded me to ‘jot down’ the mix for the grey.

‘In case the chairs get chipped again,’ she said, and Hugo and I had ‘left town’.

I never shared my paint mixes with anyone, but she knew exactly when to catch me off guard and I scribbled it down on the back of an envelope just to get her off my back. Oh, she was a crafty girl.

The party for Nikki’s dining room was a great success and the perfect launch pad for my shop, which was opening the following week. I handed my new business cards to everyone there. ‘Anteeks – Fine Junque and Objects of Charm’, they said, in elegant grey type, with the address and phone numbers and stuff.

The silly name had been Hugo’s idea and I liked it, because it didn’t sound like I was taking myself too seriously – and with all the proper grown-up antique shops round the corner on Queen Street, I thought I’d better make that clear.

It seemed to work. In no time all the key newspaper sections and magazines had rung up wanting to do features about me and the shop. I was happy to oblige and called Hugo and Tom in as extras on some of the pictures.

The shop looked great – if I do say so myself – and it hadn’

t cost me much to do it up at all. I had found some great cabinets in an old draper’s shop in Newcastle – the one up the New South Wales coast, not the one back in England where the boats come in – and tacked cheap pine trims on the front and painted them all matt white. With a couple of grey-painted salon chairs it was instant Christian Dior goes boho.

Hugo and Tom helped me paint the floor the same pale grey, which was a very funny, messy day, and I made an ‘Anteeks’ shop sign out of a mixture of old commercial letters I had found here and there, in a funky jumble of colours and sizes. It looked very charming.

The night before it opened, Tom, Hugo and I had a picnic dinner in there and toasted its success with champagne. Tom had drawn me a special advertising notice to encourage customers, using his best felt tips.

‘Nice things! Groovy shop! Charming! Good stuff! Tom’s mummy!’ it said, with a picture of me holding a big yellow and white spotty jug he’d found for me all by himself, hidden away in a cupboard in a junk palace up the Pacific Highway.

I put his poster in the window, surrounded by the display of yellow jugs and vases, Tom’s spotty one full of crabapple branches with the fruit still attached. It looked very fine and from the first morning, Anteeks was a roaring success.

Having a shop was just as much fun as I’d hoped it would be. All kinds of people popped in and it was very sociable. Hugo would sneak out from the office and have tea with me some afternoons, bringing me a slice of orange cake from our favourite café, Agostini’s, which made it seem naughty and wicked, like a midnight feast.

Used to being master of my own time, I did find it a bit of a juggling act with Tom at first and had to shut up shop whenever I had to go and pick him up from school, or take him to the dentist, which I knew wasn’t great for business. Sometimes I had to shut completely for a couple of days while I went hunting for new stock, but it seemed to work out. People seemed to accept that quirky opening hours were just part of the Anteeks experience.

The Scent of You

The Scent of You Evangeline Wish Keeper's Helper

Evangeline Wish Keeper's Helper How to Break Your Own Heart

How to Break Your Own Heart The GoMo

The GoMo Secret Keeping for Beginners

Secret Keeping for Beginners Pants on Fire

Pants on Fire Mad About the Boy

Mad About the Boy Handbags and Gladrags

Handbags and Gladrags Cents and Sensibility

Cents and Sensibility